The world became accustomed to double-digit growth in China. But such growth wasn’t sustainable, as Europe and the US struggle with debt. Analysts concede that China’s growth, fueled by easy credit, is slowing. Yale lecturer and author Vikram Mansharamani outlines the implications: In recent years, China has snapped up a lion’s share of commodities – steel, cement, aluminum, iron ore – and now demand is slowing. Inventories are piling up in China’s factories and ports. Emerging economies that contribute to China’s supply chain will feel the pinch. “A material slowdown in China will affect other emerging markets despite arguments about decoupling,” Mansharamani reports, adding that pooled funds have created more financial connections than ever before. Investors who counted on heavy growth for China and its suppliers can expect a portfolio hit. Predictions that China would surpass the US as the world’s largest economy could be off by years or decades. Mansharamani expects China’s leaders to direct resources at promoting social stability, encouraging consumption and ultimately strengthening the economy. – YaleGlobal

Slow growth could help China’s economy, but hurt mining, supply chain and investors

Over the past three years, there’s been a remarkable transformation in global perceptions about the sustainability of Chinese growth. As Europe faltered and the US fought a massively oversupplied housing market, China managed to sail through difficult global economic conditions and seemingly avoided the difficulties that ensnared much of the West. In 2010, the world was convinced that Chinese economic growth would save the world. China had grown to become the world's second largest economy and many extrapolated this trend to the day that China would be larger than the United States. Few questioned this belief, and investors titled their portfolios towards assets that would fare well in a world of strong continued Chinese growth.

The sustainability of China's high growth rates is now being questioned, and with good reason. Headline GDP growth was 7.6 percent in the most recent quarter, the sixth straight quarter of slowing growth. Chinese officials at the highest levels regularly comment today about measures to support continued growth. Benchmark interest rates were cut in June and July, and while real estate markets have recently demonstrated some resilience, prices remain – on average – below last year's levels and inventories are noticeably high. Recent earnings reports from multinational corporations continue to confirm the official data: China is slowing, with significant implications.

The credit-fueled investment boom is ending, with serious ramifications for the supply-chain to China. The short of it is that China has simply built too much stuff, and while it will eventually need the currently empty malls, buildings and infrastructure – one can even add entire cities to this list! – demand for the raw materials used to build them will plunge. Given that approximately 75 percent or so of recent Chinese GDP growth has come from capital investing, building less stuff in China has the potential to cut growth rates to the low- or mid-single-digit range.

While the list of casualties may be quite long, three of Wall Street’s favorite investments appear particularly vulnerable; two other expected “casualties” may actually stumble through without much pain.

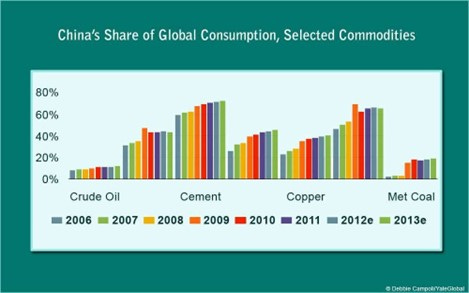

Figure 1. Big consumer: Investors fear that China’s purchases of raw materials will plunge

As a result of its building boom, China has had a domineering influence on the market for industrial commodities. The magnitude of Chinese demand on selected industrial commodities is noteworthy: more than 60 percent of global demand for cement and iron ore, more than 40 percent for steel and aluminum in 2011. Inspired by strong growth in demand for their products over the past several years, many mining companies have embarked on multiyear expansion projects – with an underlying assumption of continued growth in Chinese demand.

Reduced demand from China combined with expanded supply will lower prices. Consider iron ore, selling for ~$50/ton in 2007. In 2011, it was trading for ~$200/ton at one point and was recently quoted ~$110/ton. If the Chinese building boom busts, demand for iron ore, a key input in steel-making, will surely plunge. Iron ore could revisit the ~$50/ton price point, if not lower. In general, however, it’s conceivable that India and other emerging markets could pick up the slack capacity of what are fundamentally scarce resources in the long-run – more than 5 years).

Australia, in particular, is in the cross-hairs of a slowdown in Chinese investment spending as it’s a major supplier of key industrial commodities – bauxite, alumina, gold iron ore, lead, zinc, uranium, aluminum, brown coal and more. Years of strong growth from China have also led to a continued influx of immigrants participating in the booming mining business, resulting in inflationary pressures in both labor and housing markets. Many of the Australian mines have expanded to meet an expectation of continued Chinese demand growth.

The risk of commodity weakness infecting Australia's banking and housing finance system is quite high because most mortgages are kept on the books of banks. Investors should exercise caution when investing in Australian assets -- be they equities, debt, or even the Australian dollar (Figure 2). As a relatively high-yielding option in a low-yield world, Australian sovereign debt has benefited from strong inflows of yield- hungry capital. Mid-single digit yields, sufficiently attractive to date, may not appear adequate in the face of currency declines exceeding the yield.

A material slowdown in China will affect other emerging markets despite arguments about decoupling. Even if one believes that the real economies of the emerging markets have decoupled due to domestic consumption drivers – though in China, for instance, consumption accounts for about a third of GDP (versus more than 50 percent in both India and Korea) – it’s clear that the financial markets remain interconnected. In fact, if anything, the emergence of exchange-traded funds and other pooled investing products has created greater financial interconnections than ever before.

Further, the mere fact that India, China, Russia, Thailand and other developing countries are pooled into a single asset class known as "emerging markets" connects them via portfolio managers that view them as linked. If Russia were to fall by 20 percent, for instance, and all other markets were flat, emerging-markets managers would find themselves overweight non-Russia markets. Indiscriminate selling might follow as portfolio managers rebalanced, generating the financial contagion all desperately sought to avoid.

In addition, approximately 25 percent of the S&P 500's earnings is directly derived from emerging markets, with a large amount (perhaps around 20 percent), coming indirectly from emerging markets. Unfortunately, this means that multinational corporations may soon find that earnings are harder to grow than previously expected.

While it is not impossible, it seems unlikely that the world is about to descend into a multi-decade debt- deflation spiral. Some areas may not be so vulnerable.

A credit-fueled investment boom is ending, with serious ramifications for the supply- chain to China

Paradoxically, China probably won’t be a severe casualty of a massive deceleration in investment spending. Social stability is on the top of Chinese leaders’ minds, particularly as the country goes through a leadership transition. They will deploy all resources at their disposal to prevent social unrest that might emerge from slower economic growth. And even if the country grows GDP at roughly 3 to 5 percent per annum over the next decade, that’s impressive growth that will result in a significantly larger middle class: Consumption as a percentage of GDP is destined to rise, creating winners amidst the wreckage and placing the Chinese economy on a more resilient foundation.

Several commodities are not as affected by the China factor as industrial commodities, specifically agricultural and energy commodities. The middle classes of India and China are growing rapidly, even if GDP rates slow in these countries, and accompanying this growth is demand for animal protein and transportation fuels. Families, accustomed to adding some chicken or pork on top of their rice for dinner, are unlikely to cut back to just rice. Likewise, the demand shock to energy is growing as individuals go from riding bikes to mopeds, to motorcycles and cars. Such demand trends are unlikely to reverse. Hence, the globe can anticipate higher prices for food and fuel commodities for the foreseeable future.

Last year, most analysts expected the Chinese economy to eclipse the US economy within 10 years. The combination of a rapid Chinese slowdown and a US renaissance driven by American agriculture and natural gas, i.e, food and fuel, may in fact push the crossover date out by years, if not decades – making analyst credibility perhaps the most visible of casualties.

Vikram Mansharamani is a lecturer at Yale University and the author of Boombustology: Spotting Financial Bubbles Before They Burst. Follow him on Twitter @mansharamani Copyright © 2012 Yale Center for the Study of Globalization