Fatty Fruit Boom Drives Climate Change and Crime

Despite being a staple of Mexican diets for thousands of years, the avocado has enjoyed a global surge in popularity over the last few years. Today, the avocado market is booming. It’s gone from an exotic fruit (yes, it’s a fruit…actually, a berry) to a mainstay on menus. In fact, avocado toast has become so common it now appears on the menu of McDonald’s restaurants in Japan. And after years of suffering the indignity of not having its own digital character, social media efforts and online petitions earlier this year successfully convinced Apple to include an avocado emoji in its latest iOS release.

But the avocado wasn’t always a dining darling. In fact, as noted by NPR, it took innovative marketing efforts of California growers in the early 1900s to drive its current mass-market appeal. These farmers met to discuss how they might overcome the challenge of the fruit’s name: it was then called ahuacate, the Aztec word for testicle, which was not particularly easy to pronounce. It had also been colloquially called “alligator pear,” an equally unappealing name. Their solution was to rename the fruit, and from then on, it was known as an avocado.

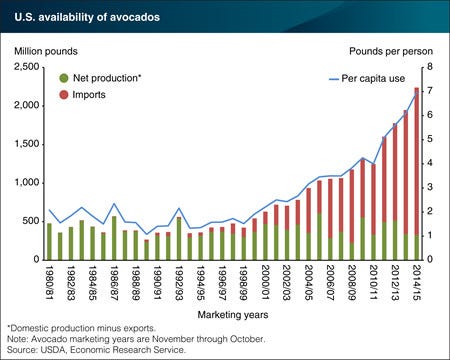

Demand grew steadily and really began to accelerate over the last fifteen years. According to the USDA, American per capita consumption of avocados rose from 2 pounds per person to over 7 pounds per person between 2000 and 2015, meaning the US consumes well over 4 billion avocados per year. This growth, notes the Washington Post, was driven by the loosening of restrictions on imports from Mexico, a surging Hispanic population in the United States, and the avocado’s association with healthfulness.

And it’s not just America that has fallen in love with avocados. British café operator Pret-A-Manger noted that avocado was its fastest growing ingredient in 2015 and helped push sales to a record high. In addition, London is also home to the world’s first “all-avocado” restaurant. (Call me a rebel, but I’d probably sneak in a chip or two!) Australians are also eating ever-increasing volumes of the fruit. Over the past twelve years, per capita consumption has risen from around 3 pounds per capita per year to over 6.5 pounds. And growth in demand for avocados is booming in China, albeit from a very low base.

On the supply side, weather and other factors have disrupted the steady growth needed to meet demand. The drought affecting California, for instance, has hurt avocado production – but not in the way you might expect. As northern California water is less available, San Diego farmers have come to depend on water from the Colorado River. Except that water has more salt, and avocado trees are very sensitive to salt. The result: smaller fruit. San Diego had been America’s avocado capital, producing more fruit from the 18,000 acres of avocado trees than any other county in the country. In Mexico, a work stoppage earlier this year virtually stopped exports from the world’s largest avocado producing region, creating what commentators called the “great guac crisis of 2016.”

In Asia, both New Zealand and Australia suffered from weather-related growing disruptions that took supply down by around 30%, driving avocado prices to over US$4 in Australia earlier this year. And given Mexico’s importance in the avocado trade, the July to October disruption of its exports translated into higher prices. The price of a 48-count case of avocados surged from around $45 to $100 in the United States, leading retailers to increase prices by more than 100%. In some cases, restaurants were unable to secure any avocados. As a result, American regulators have proposed importing avocados from Colombia to address the shortage amidst unending demand growth.

The price of a 48-count case of avocados surged from around $45 to $100 in the United States

But like with all great booms, there are unexpected consequences. First, there’s climate change. According to Newsweek, a small plot of avocado trees can generate up to $500,000 a year. As more and more Mexicans seek to profit from global demand, they’ve been destroying forests to plant avocado trees. Vast swaths of pine and fir trees are being illegally cut down. The deforestation has already impacted the monarch butterfly and water flow patterns. According to experts, a mature avocado orchard uses twice the water of a dense forest. And local residents are complaining that the incidence of breathing and stomach illnesses has risen as pesticides used in the mountain orchards have made their way into water supplies.

Second, the combination of strong demand, high prices, and regular disruptions to supply has generated a strong incentive to traffic in avocados. The economics have also attracted some nefarious actors, leading to gang warfare in the Michoacán state of Mexico. It’s estimated that 80% of the avocados consumed in the United States are from this area, and because of the violence the business has generated, some now refer to fruit from the state as “blood avocados.” Separately, high prices have led thieves in New Zealand to steal cases of avocados from growers and sell them on the black market.

So what can we do about these dynamics? Is there a way to mitigate the footprint of our avocado-consuming addiction? One opportunity to consider is an expansion of avocado orchards in Florida. The state has plenty of water, a hospitable climate, and is dealing with a collapse of its citrus industry. We might even take the locavore movement to its logical end and grow our own avocado trees. They’re apparently easy to plant and grow quite quickly. They can help offset the cost of a SuperBowl party, and given the Aztecs believed the avocado was an aphrodisiac, your plant may also prove useful on Valentine’s Day.

Vikram Mansharamani is the President of Kelan Advisors, LLC and the author of Boombustology: Spotting Financial Bubbles Before They Burst (Wiley, 2011). To learn more about him or to subscribe to his free mailing list, visit his website. He can also be followed on Twitter @mansharamani or by liking his Facebook page.