Scrapping the cedi could lift Ghana’s confidence and GDP, but only citizens can stop corruption

Dream of gold: Ghana soccer team celebrates qualifying for 2014 World Cup, but threatened not to play unless wages were delivered to Brazil in cash (top); the poor dig for gold in Ghana, Africa's second-largest producer of the precious metal

NEW HAVEN: As famed US investor Warren Buffett has aptly stated, “it’s only when the tide goes out that you can see who is swimming naked.” Ghana is swimming naked, to put it bluntly, and this is increasingly obvious to the world. With its currency, the cedi, fast becoming not worth the paper it is printed on, Ghana’s salvation may have to come from embracing the US dollar.

A mere two years ago, Ghana had been hailed as the world’s fastest growing economy. Today, the country is seeking help from the International Monetary Fund to navigate a nasty economic slowdown, and 70 percent of the government budget is spent on supporting an inflated bureaucracy. Ordinary citizens lack basic infrastructure, and as a result of poor sewage and sanitation, the country is experiencing a cholera outbreak approaching epidemic levels.

Not surprisingly, confidence has plunged. Capital has fled, and the near 30 percent drop in the value of the cedi relative to the dollar this year has shaken the faith of even the most dedicated Ghanaian business leaders. Recent surveys suggest business confidence in Ghana has fallen from over 90 percent to 20 percent over the past few years. Unfortunately, the confidence problem is compounding, as seen in the recent game of domestic brinkmanship embarrassingly played out for a global audience during this year’s World Cup.

In June, the Ghana World Cup team, having lost faith in their own government’s ability and willingness to pay, demanded that the Republic of Ghana fund their appearance fees in cash immediately – or they would refuse to play in their next scheduled match. Fearing global public embarrassment, President John Mahama acquiesced and delivered about $3 million in cash on a chartered flight from Accra to Brasilia to meet the players’ demands. With the drama of reality television show, reporters from global news agencies literally followed the money from the airport to the players. The events inspired a Hollywood screenwriter to begin developing a fictional account of the relay, though classifying the film as suspense, comedy, thriller or tragedy may prove a difficult task!

Missed economic opportunities are a common discussion topic these days, with commentators regularly highlighting Japan’s lost decades, Europe’s deflationary dynamics and America’s lackluster labor markets. But when it comes to genuinely lost decades and foregone economic opportunity, Ghana is a serious contender for first prize.

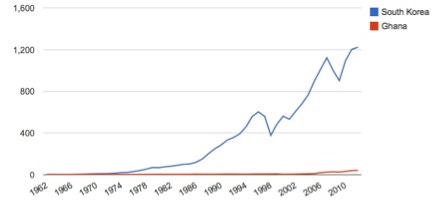

Fifty years ago, Ghana boasted a per capita GDP roughly comparable to that of South Korea (Figure 1). Both countries had about 60 percent of the labor pool in agriculture. Today, South Korea has a GDP almost 30 times that of Ghana. Unlike South Korea, Ghana has been blessed with natural resources, ranging from gold to fertile land. The commodity boom of the 2000s supported strong growth and when offshore oil was discovered, it seemed Ghana’s fate had finally turned. Optimism reigned and by 2011 the country became a poster child for Africa’s resurgence. Confidence was running high, possibly too high, and by 2013 in a classic sign of entrepreneurial hubris and overconfidence, a developer proposed building the skyscraper complex Hope City, a US$10 billion development. At that time, the cost of the proposed development represented more than 20 percent of the country’s GDP.

Political stability had been elusive for several decades, but appears to have tentatively taken hold, and ballot-box battles appear more likely than the once frequent barrack-mobilized coup d’états. Nevertheless, several leaders have privately expressed concern that the country’s woes may in fact inspire a non-democratic leadership transition. Ghana’s coups took place for many reasons, but chief among them was the military’s desire to clean up a corrupt and ineffective government, ridding the country of an administration failing to meet the needs of Ghanaian citizens or address social injustices. In this regard, Ghana’s leaders should take notice.

The economy and government budget remain heavily dependent upon gold production, and 2013’s rapidly retreating gold price exposed economic weakness. The lack of accountability is on full display. Consider admissions from the auditor-general that the government has lost more than US$1 billion to payroll fraud and non-existent civil servants – an amount roughly equivalent to the donor aid received by the country. A recent program intended to support development in the northern portion of the country involved significant capital invested in a guinea fowl farm. Government auditors arrived to confirm the farm’s progress and found no fowl. “They’ve flown to Burkina Faso,” noted a farmer.

The government admits that it does not have adequate systems to track payments and recently retained KPMG to assist in auditing personnel. Surely ordinary Ghanaian citizens are not blind to such waste.

It is useful to summarize recent comments given by Mensa Otabil, one of the country’s most influential and respected thinkers, at the Festival of Ideas conference that took place in Accra in August. Otabil drew comparisons between the Titantic and Ghana’s prospects and between the ship’s overconfident captain and Ghana’s leadership. He urged leaders to acknowledge the gravity of the situation and accept losses while saving whatever possible.

The roots of Ghana’s woes are too numerous to address in any one policy, but it does appear that the currency may have outlived its useful life. Originally intended to provide a sovereign means of exchange, today it is a source of uncertainty and highlights the country’s inability to constrain spending and maintain fiscal and monetary discipline. Ghana should scrap the cedi.

The cedi has depreciated by more than 99.99 percent since its formal adoption in 1967 (Figure 2). US$10,000 converted into cedi at that time would today be worth approximately US 30 cents. Few, if any, have faith in this currency. Classic business strategy suggests that a company outsource whatever is not core to its competence. Why not outsource the currency and attendant monetary policy? While the US dollar provides one option, almost any stable alternative to the cedi will do.

In fact, some of the economy has de facto dollarized already. Many individuals and companies think in dollar-terms and simply use the conversion rate to price in local terms. This should make a transition away from the cedi easier to adopt and less disruptive than Ghanaian leaders may fear. While the success of Ghana’s recent Eurobond offering, oversubscribed three times, is compelling evidence of the global search for yield, it also provides strong support for the argument that cedi risks remain high on investor minds. Although Ghana’s medium-to-long run economic outlook is promising, it’s unlikely a cedi-denominated bond would have attracted such demand.

The benefits of outsourcing monetary policy have been visible from Hong Kong to Zimbabwe to Ecuador. Adopting the US dollar has squashed inflation, encouraged growth, enhanced monetary credibility, and helped attract foreign capital back into the country. The greenback is not, however, able to eliminate corruption and inefficiency – something citizens must work on themselves. Ghanaians must pay taxes – might the world cup event have been an elaborate tax-avoidance scheme? – and demand government accountability. Simply dollarizing won’t do that. Such changes can only come from within.

Using Otabil’s analogy, the Ghanaian ship is sinking, and bold leadership is required. Outsourcing the currency may bring much-needed fiscal and monetary sobriety – and a lifeline that just may buy enough time for Ghana to save itself.

Vikram Mansharamani, PhD, is a lecturer in the Program on Ethics, Politics, & Economics at Yale University, a senior fellow at the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business & Government at the Harvard Kennedy School, and the author of Boombustology: Spotting Financial Bubbles Before They Burst (Wiley, 2011). He recently returned from a trip to Ghana.