The world’s two biggest democracies do not reach full potential on trade or other common interests

Ranging from investment and trade to defense cooperation enormous opportunities exist for both sides to create a mutually beneficial and balanced relationship.

Direct economic cooperation is an obvious area for collaboration. India needs infrastructure and power, for instance, and US companies want foreign markets. India has a globally competitive IT talent pool, and US enterprises are on an unending search for technical knowhow. Consider the collaboration opportunities of merging Indian IT talent with US automobile manufacturers as data from billions of automobile sensors explode in volume, generating what is expected to be the second fastest growing segment of the emerging big-data market.

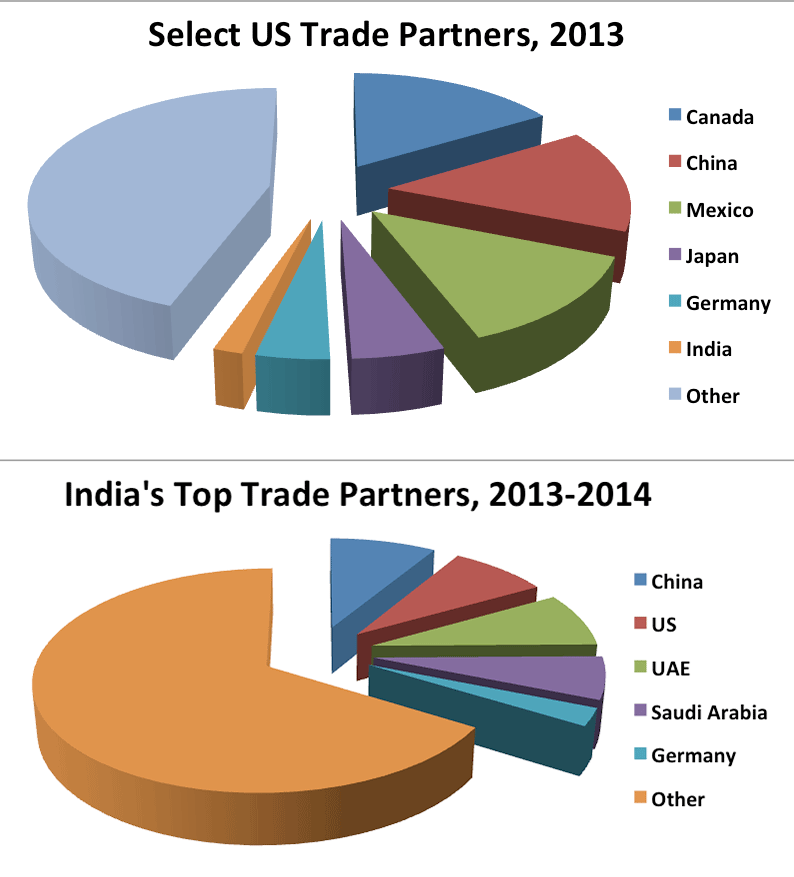

Further, India’s desire to increase its manufacturing capacity may align with American desires to diversify from China, where average hourly earnings now exceed $3.52, versus 92 cents in India. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been marketing India as having three ingredients US companies seek: demand for goods, attractive demographics and a democratic regime. The direct economic benefits of trade and investment will accrue to both Indian and Americans.

China’s economic slowdown provides a powerful tailwind for India’s economy. As the credit-fueled Chinese investment boom ends, the entire supply chain of raw materials fed into its building boom is vulnerable, creating lower prices for many investment commodities – iron ore, lead, steel, zinc, copper and more. Thus, the Chinese slowdown has reduced the prices of many of the natural resources upon which India depends, lowering inflationary pressures within India, and thereby creating room for rate cuts that can spur economic growth. It allows India to remove subsidies and address trade disputes to allow further liberalization. It’s unlikely the November agreement between the United States and India allowing stockpiling to address food-security issues would have been reached in an environment of high food prices. The resolution of this lingering dispute breaks a deadlock holding up global trade talks.

India needs energy, and as the United States allows increasing volumes of crude exports, why shouldn’t the US consider a long-term supply agreement with India? Doing so would solidify relationships with a large, growing market. India would become less dependent upon Russia and Iran, removing a key market from these struggling oil economies.

At a time when much of the western world laments the ills of capitalism gone wild, India is disposing of Soviet-style planning agencies – Modi disposed of the 5-year plans during his first Independence Day speech – and rushing headlong into increasingly capitalist policies. In 1992, Deng Xiaoping kicked off an explosion of Chinese economic reform around the mantra “to get rich is glorious” – an economic turning point that resulted in staggering growth over the next decades, as suggested by some Sinologists. Modi’s turn towards capitalism and away from socialist policies has a similarly transformative economic reform agenda, one organized around the mantra “to get efficient is glorious.” If Modi and his team can help get India out of its own way, there’s no reason the country can’t become the fastest growing large economy in the world. Participating in and encouraging this growth is in America’s interest.

A leading obstacle to faster growth is India’s problematic relationship with Pakistan, an association that has focused upon the Kashmir territorial dispute since independence in 1947. Pakistani relations with India chilled noticeably following the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks attributed to Lashkar-e-Taiba, a terror group that operates from the region. India, Pakistan and the United States would benefit from a more stable and prosperous Pakistani economy. Modi invited pro-business Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to attend his inauguration, and relations were improving until Pakistan courts granted bail to an accused terrorist involved in the Mumbai attacks.

Modi’s powerful electoral mandate opens the opportunity for an innovative reengineering of the India-Pakistan relationship, the basis of which can be increased bilateral trade. His identity as a Hindu nationalist offers potential political cover from domestic Indian opposition to increased collaboration with Pakistan; his bluntly stated objective of accelerating economic growth may mitigate Pakistani concerns of his ultimate goal. Modi is the first Indian prime minister born to an independent India, and brings a refreshingly focused and open mind to the issues. Pakistan’s Sharif is equally interested in economic progress. Vibrant Pakistan-India trade has the potential to build mutual trust and might ultimately improve political relations – developments that are good for Pakistan, India and the United States.

The United States can and should encourage such developments by offering incentives for both parties and simultaneously increasing counterterrorism collaboration with both nations to alleviate ongoing concerns. It might even consider deepening military ties with both nations as a means to both diffuse potential Pakistan-India hostilities as well as deter an ambitious China from getting militarily aggressive.

Richard Haas, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, recently described US-India relations while introducing Modi at a CFR event: “The bilateral relationship is potentially one of the most important for the United States…. The challenge and the opportunity for both countries… is to translate all this potential into reality.”

One of the main challenges is to overcome the stigma of four recent bilateral flare-ups – each provides compelling evidence of an immature relationship that still requires effort. First, the spectacular momentum generated by President George Bush’s civil nuclear agreement was lost when India passed a nuclear liability law that de facto prevented US commercial participation in the Indian civil-nuclear industry. Second, the Indian imposition of protectionist policies and taxes on foreigners generated trade disputes that derailed progress. Third, Modi’s ascent reminded the world that the United States had barred the former Gujrat minister from entering the country because of his supposed role in 2002 riots that left about 1,000 dead, mostly Muslims. Lastly, diplomatic hoopla surrounded the arrest and strip-search of Devyani Khobragade, India’s deputy consul general in New York. India escalated tensions by lessening security for US government employees in New Delhi.

Another challenge stems from areas where American and Indian interests diverge. Consider India’s dependence upon foreign energy supplies, defense equipment, power technologies and its prickly nationalism born of centuries of colonial rule. These factors create Indian alliances that run counter to US interests, particularly the India-Russia relationship. In December, Russian oil giant Rosneft signed a 10-year crude-oil supply agreement with India’s Essar Oil, and the Russian state-owned Rosatom agreed to build 12 nuclear reactors for civilian power generation in India. Along with these announcements came Modi’s public assurances that Russia would remain India’s top defense supplier. A simultaneous announcement stated that India would build 400 Russian Ka226-T twin-engine multi-role helicopters a year.

Both countries should look beyond these speed bumps, because the blunt reality is the United States needs India – as a beacon of democratic capitalism in a strategically and militarily critical part of the world. The blunt reality for India is that it needs the United States – as an economic and military superpower capable of assisting the quest to achieve peer status. While the many hiccups over the years have raised concerns about each country’s ultimate commitment to the other, the commonalities of interests are overwhelming and the impetus to convert the potential of shared values into a functional reality is urgent.

Vikram Mansharamani is a lecturer in the Program on Ethics, Politics, & Economics at Yale University and a senior fellow at the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government at the Harvard Kennedy School. Follow him @mansharamani