Panama Drought Creates Global Traffic Jam

Sustained congestion at the Panama Canal could ripple through global supply chains

Last week, I had the opportunity to visit the Panama Canal, one of the most strategic waterways in the Western Hemisphere. It sits at the literal crossroads of North and South America as well as the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. A meaningful percentage of global trade, worth approximately $270 billion, transits the isthmus in Central America each day. In 2022, more than 14,000 vessels went through the canal, most of which were container ships carrying goods between Asia and the American east coast or Europe. And the strategic value of the Panama Canal is substantial, allowing for rapid naval movements that would otherwise be hampered by a lengthy journey around the southern tip of South America.

The economic and strategic value of a waterway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific oceans motivated potential canal builders going back as far back as the 1500s when the Spanish Crown sought to unite both seas. The French made numerous attempts to build a canal in the 1800s, but as the century came to an end, so too did their funding. Further, most attempts to construct the canal led to debilitating disease and illness among the workers.

That’s when America was persuaded to abandon a waterway connecting the oceans through Nicaragua. But when Colombia failed to ratify the treaty granting a ten-mile wide stretch across the isthmus to the United States for the construction of a canal, US President Teddy Roosevelt supported Panama’s independence from Colombia in 1903, and secured the future of the Panama Canal.

Turns out that the key challenge in constructing the canal was worker health, specifically yellow fever and malaria. And it was American doctors that solved the problem by focusing on controlling disease-carrying mosquitos. By 1914, the canal was completed and on August 14th of that year, the Ancon successful navigated the interoceanic waterway that was owned, controlled, and managed by the United States.

Over the next few decades, tensions rose as Panamanians sought a modification of the treaty that granted sovereignty over the Canal Zone to America. These efforts culminated in US President Jimmy Carter agreeing to give full ownership and control of the canal and surrounding lands to Panama in 1999.

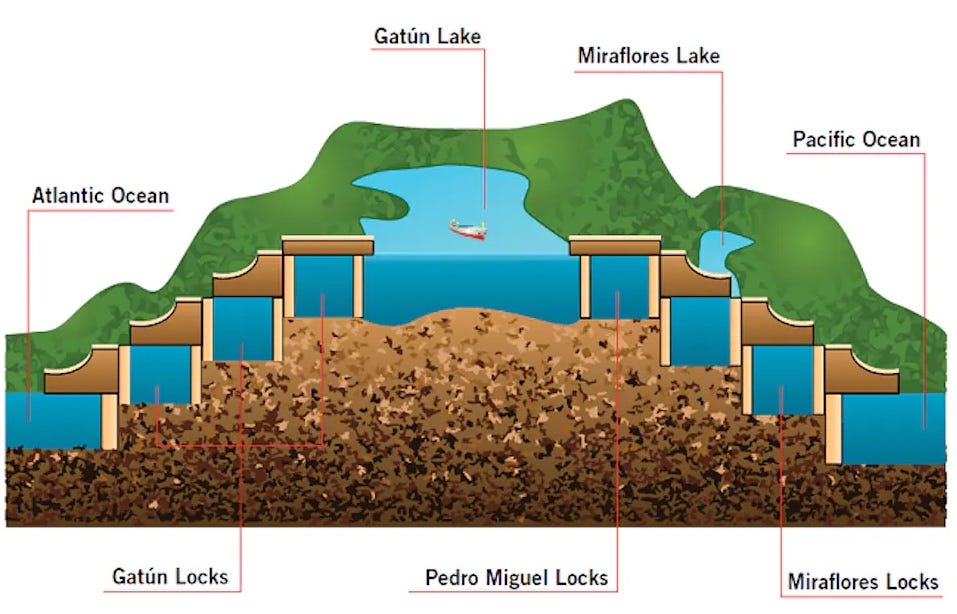

The canal is an engineering marvel that enables gigantic ships containing vehicles, petroleum products, bulk commodities, and cruise passengers to rise 26 meters (~85 feet) above sea level in order to cross between the oceans. The design of the canal involved creating a manmade lake at the highest point, which allows gravity to move water into the locks as needed.

During my visit to the Miraflores Locks, I watched a gigantic oil tanker get lifted by 26 million gallons of water that flowed in its chamber in about 10 minutes. And here's the part I found fascinating: not one pump is used to move even a drop of water. Gravity does all the work. But as you can see on the schematic above, this is only possible because of the water held in Gatun Lake. On average, each ship that passes through the canal results in 55 million gallons of water being flushed out to sea. Each day, the canal uses three times the water used by New York City.

One of the concerns I’ve had for a few years (See #6 on my list of global predictions for 2022-2027) is that canal operations are at risk of disruption if Panama suffers a drought. Unfortunately, that’s exactly what’s happened. Leaders at the Panama Canal Authority are restricting ship weights and reducing the number of daily crossings in a quest to conserve water. As a result, there’s now a traffic jam of vessels waiting to enter the canal.

The congestion is now causing ripples throughout global supply chains. A recent Reuters report summarized the issue and its impact:

Ship owners are getting so desperate that some are paying millions to avoid the congestion. According to Business Insider, “a $2.4 million price tag was the winning bid for an auction held by the canal authorities for vessels to secure slots to sail through the waterway.”

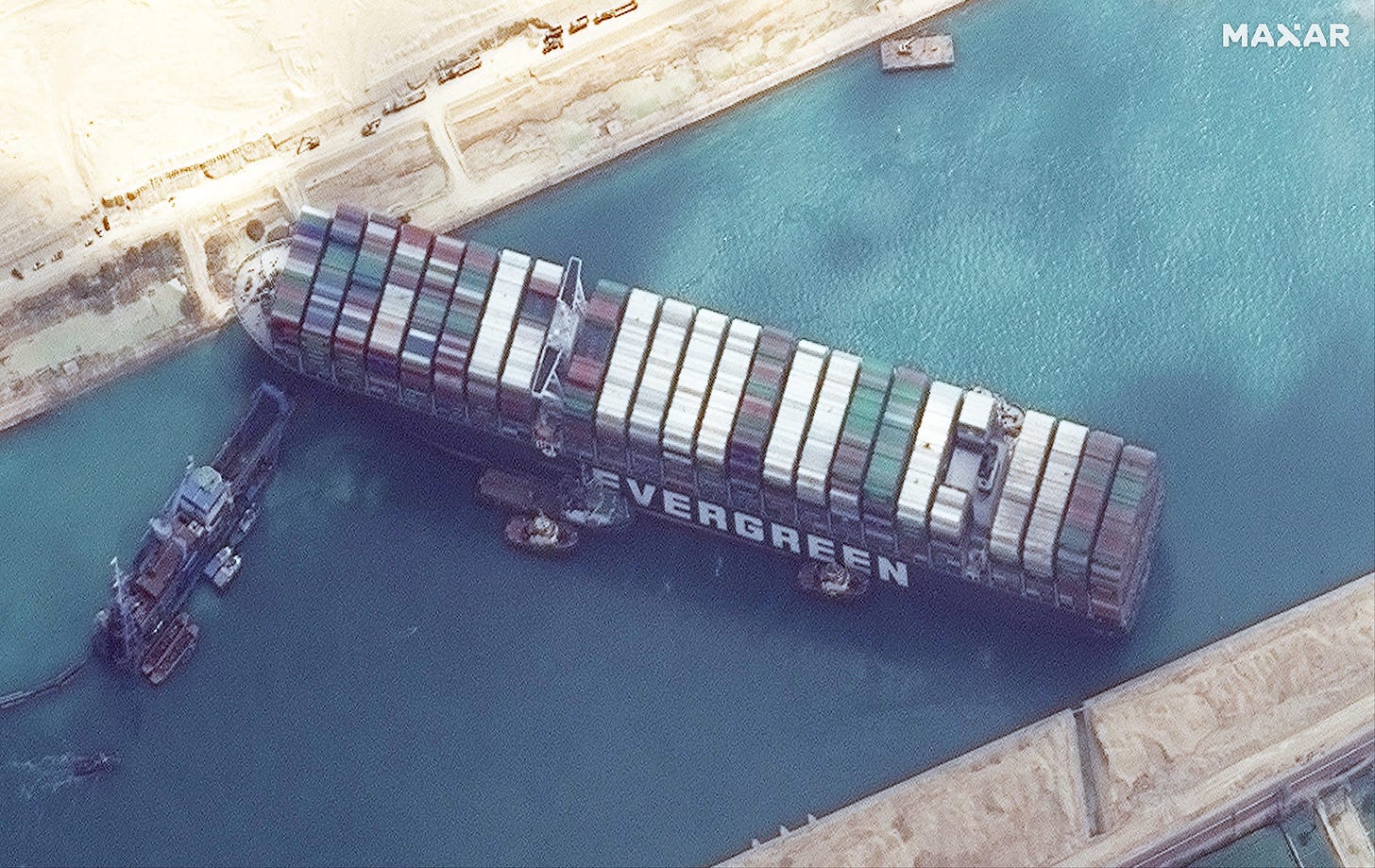

Of course, insufficient water is not the only potential risk to the Panama Canal. In 2010, extraordinarily heavy rains caused Gatun Lake to overflow and the flooding that followed forced a closure of the canal as the locks were inundated. And as we saw in 2021, it’s also possible for a ship to get stuck in the canal. In March of that year, the Suez Canal was blocked for six days by the Ever Given, a massive container ship. A mere five days after its grounding, the traffic jam had more than 369 vessels queuing to pass through the canal, holding up about $10 billion worth of goods each day, in a passageway that regularly handles more than 10% of global trade each day. (Incidentally, a year after this happened, the Ever Forward grounded itself in Chesapeake Bay.)

There’s also the obvious military risk associated with strategic bottlenecks. In 1967, the Suez Canal was blocked by Egyptian forces at the onset of the Six-Day War and remain closed until after the Yom Kippur War. It wasn’t until after US and British minesweepers cleared the Suez Canal in 1974 that Egypt reopened the canal. Given the strategic importance of the Panama Canal, it’s noteworthy that the commander of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s navy, Rear Admiral Shahram Irani, stated bluntly “We are planning to be present in the Panama Canal” in January of this year. The Islamic regime, one of the world’s most extreme sponsors of terror, then sent two warships to the Western hemisphere, the Dena and the Makran. According to the Tehran Times, “Dena is a Mowj-class warship that...is outfitted with anti-ship cruise missiles, torpedoes and naval cannons. Makran, a forward base ship weighing 121,000 tons, is…used to support the combat vessels logistically and can carry five helicopters.”

The drought in Panama and security risks are also motivating many to reconsider alternatives to the Panama Canal. Going back to the late 1800s, there has always consistent interest in constructing a canal through Nicaragua. In fact, a Chinese firm suggested it would do so in 2013 and secured a 50 year concession to build the canal at an estimated cost of ~$40 billion. And just last year during his Independence Day speech, Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega noted that “the canal will be a reality at some point.” (I’m not holding my breath, see #13 on my list of global predictions for 2015-2020.)

Another option that has been kicked around since the 1970s is the construction of a huge interconnected network of railways, highways, and pipelines to create a land bridge across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Southern Mexico. President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador almost tripled funding for the project in 2024 and has suggested it could compete with the Panama Canal.

And late last year, Florida-based Zergatran proposed a green shipping corridor in Colombia that would use an underground maglev train and automated ports to transfer containers between the oceans in less than 30 minutes via route in the far north of Colombia. The company is in the midst of trying to raise money for the project, and offers a futuristic vision that has yet to get much attention.

While it’s unclear how these dynamics will ultimately play out, I continue to watch closely for the impact they may have on the global economy. If this turns out to be a short term blip, then we may not notice any meaningful impact. If, however, congestion continues or additional disruptions surface, it’s worth paying attention to the following potential ramifications:

The rising tensions and risks in the Panama Canal provide further incentives for global manufacturing to shorten supply chains, and to shift them towards friendly territories. The friendshoring trend remains in tact, and may in fact accelerate if canal disruptions increase. Mexico may continue to be benefit as the manufacturers seek to move operations closer to US markets. And supply chain strategies will continue to shift away from just-in-time approaches to ones that adopt a just-in-case logic. Resilience will trump efficiency as a criteria for strategy

The ripples from congestion in the Panama Canal may create port disruptions as shippers adjust routes. While container ships have been least affected to date, the longer the disruption continues, the more likely it becomes that goods are sent to West Coast ports instead of East Coast ones. The global transportation system is not designed to dynamically handle surging and shrinking demand and this could wreak havoc on trucking and rails industries.

Incrementally, these dynamics point to sustained inflationary pressure with higher costs to transport goods that should make their way into consumer prices. While it’s unclear how severe the price pressure will be, a sustained canal disruption that leads to higher costs might drive central banks around the world to continue raising interest rates, compounding global economic chaos in unpredictable ways.

About Vikram Mansharamani

Dr. Mansharamani is a global generalist who tries to look beyond the short term view that tends to dominate today’s agenda. He spends his time speaking with leaders in business, government, academia, and journalism…and prides himself on voraciously consuming a wide variety of books, magazines, articles, TV shows, and podcasts. LinkedIn twice listed him as their #1 Top Voice for Global Economics and Worth profiled him on their list of the 100 Most Powerful People in Global Finance. He has taught at Yale and Harvard and has a PhD and two masters degrees from MIT. He is also the author of THINK FOR YOURSELF: Restoring Common Sense in an Age of Experts and Artificial Intelligence as well as BOOMBUSTOLOGY: Spotting Financial Bubbles Before They Burst. Follow him on Twitter or LinkedIn.