Sotheby’s Stock Price: The World’s Best Overconfidence Indicator?

Enterprising Investor, CFA Institute

Anyone who has witnessed a live auction in which bidding far exceeds pre-auction estimates or sets a new world record price understands there is something curious in the air. There is something electric, something indescribable, something magical. I believe that “something” is confidence, perhaps even overconfidence.

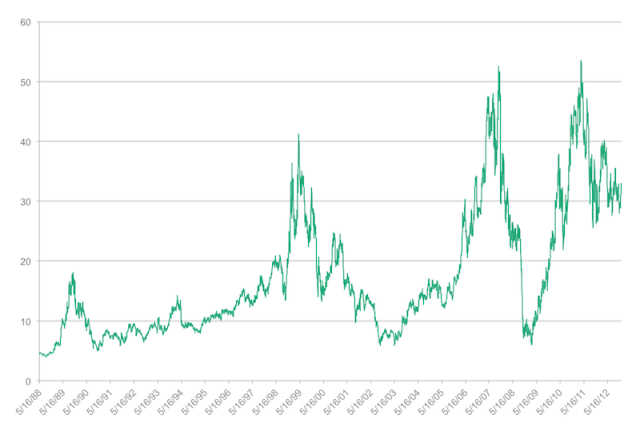

Consider the stock chart of Sotheby’s (BID:US) below, which has proven useful as a bubble indicator. A quick scan of the list of the world’s most expensive paintings finds that there are numerous chronological clusters: 1988–1990, 1997–1999, 2006–2007, and then 2011–2012. Not surprisingly, these clusters are associated with (relative) highs in the price of Sotheby’s stock. New highs in Sotheby’s stock price are an important indicator of overconfidence and bubbly conditions.

Sotheby’s (BID) Stock Prices, 1988–Present

Source: Yahoo! Finance.

At each of these times, confidence was running extremely high. In the late 1980s, for instance, Japanese art buyers domineered the market for high-end art and were responsible for numerous world record prices. Sotheby’s stock price peaked months before the Nikkei began a long decline. Likewise, the 1999 peak in Sotheby’s stock price is associated with the (irrational?) exuberance that telegraphed the tech bust. Although the buyers were different, the dynamics in 2007 were not different. Beneficiaries of easy money (hedge fund and private equity executives, among others) bought art at world record prices, driving Sotheby’s stock price to new highs. Again, the stock’s peak telegraphed the global financial crisis. The most recent peak was driven by Chinese and emerging markets buyers, possibly telegraphing a Chinese and emerging markets slowdown.

Some of my thinking about the usefulness of Sotheby’s in predicting bubbly conditions is adequately described in an article by Derek Thomson titled “The Art of Bubbles: How Sotheby’s Predicts The World Economy.” Since that piece was published, many have asked me to clarify why Sotheby’s stock price seems to telegraph bubbly conditions.

I’ll begin my answer with a question: Might the relationship between Sotheby’s stock price and bubbles merely be a coincidence? I personally do not think so, because in my eyes, Sotheby’s is a leading indicator of leading indicators of leading indicators of confidence. Specifically, there are three layers of confidence stacked upon each other that can be seen in the stock chart above: (1) buyer confidence, (2) appraiser confidence, and (3) investor confidence. Unlike the actual prices of art — which may be a reflection of buyer confidence — Sotheby’s stock price is less subject to the whims of individual buyers or of the uniqueness factor associated with specific works of art.

Not surprisingly, those that set new world record art prices tend to be those that have substantial personal resources — meaning they are usually very very rich. In short, those that pay $100mm+ for a painting are usually those that have much more than $100mm in net worth; such buyers are likely to be billionaires with significant corporate interests. Because of this connection between art buyers and corporate leadership, art markets serve as a useful indicator of corporate and global confidence. If the CEOs of major companies begin to see clouds on the economic horizon (through their corporate capacity), they are likely to scale back on their personal art buying. The inflection point when executives convert from aggressive to reluctant bidders is very unlikely to result in world record art prices. It should not be surprising, then, to note that corporate M&A activity had recent relative peaks in 1999–2000 and 2007. (There wasn’t a new M&A peak in 2011 in terms of transaction value, due in some part to the extended nature of the global credit crunch.)

Source: Dealogic.

There is an additional layer of confidence that is important to consider — auction house appraiser confidence embedded in pre-auction estimates. As new record prices are set, appraisers themselves begin increasing their estimates of what future sales should achieve. Imagine you are an appraiser of Chinese artifacts and a vase estimated to sell for between $800 and $1200 recently sells at auction for $18 million (true story!). Might you be inclined to raise your estimate of other Chinese artifacts? Higher prices yield higher estimates, which yield higher prices — until they don’t. Closely related to this appraiser confidence is management confidence. In the past, Sotheby’s management grew so confident in their appraisers that they began guaranteeing prices to prospective sellers. The result was an increase in “inventory” owned by Sotheby’s at precisely the time that the market for such art was cooling rapidly.

In addition to the buyer confidence and the appraiser confidence, there is a third form of confidence captured by the price movements of Sotheby’s: investor confidence. Because Sotheby’s stock is itself an object of investor bidding, it is a manifestation of investor perceptions and analyst estimates. As auctions go well, analysts raise earnings estimates. Higher estimates make the stock appear less expensive, drawing investor interest. Relatedly, the investor relations function at Sotheby’s exhibits variable confidence as the stock progresses and the underlying business results become obvious, thereby affecting analyst estimates.

While Sotheby’s current stock price in the low $30 per share range may not be saying very much about (over)confidence today, one can imagine a time when the stock reaches a new high. What if the stock hit $75 a share on the back of world record prices being paid by [insert country here] buyers? Furthermore, assume that the economy of [same country] were booming and its local capital markets were hitting new highs. It seems to me that it would be prudent to take a more risk-averse stance vis-à-vis investing in that country’s market.

At the end of the day, spotting bubbles is at best a probabilistic exercise and requires multiple confirmatory data points before one can say anything with conviction. Certainty is an elusive goal, but the use of multiple lenses (as I articulate in my book) can be very powerful in gaining an edge. Thus, to improve your performance in the art of spotting bubbles, focus on spotting bubbles of art.

Vikram Mansharamani

Vikram Mansharamani is an experienced global equity investor and lecturer at Yale University. He is also the author of Boombustology: Spotting Financial Bubbles Before They Burstand is a regular commentator in the financial and business media, having contributed to Bloomberg, MarketWatch, CNBC, Forbes, Fortune, the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Atlantic, Yale Global, the South China Morning Post, the Korea Times, the Khaleej Times, Harvard Business Review, and the Daily Beast, among others. Mansharamani holds a BA from Yale University, an MS in Political Science from MIT, and an MS and a PhD from the Sloan School of Management.