Specialists vs. Generalists in Asia: The Yale-NUS College Experiment

The boldest experiment in education today is taking place in Singapore. Yale-NUS College (click HERE) has been operating as a residential college focused on liberal arts and sciences in Asia since it opened its doors in 2013 and welcomed 157 students from 26 countries.

I think of Yale-NUS as an audacious experiment for two reasons. First, given the historical emphasis on memorization and rote learning of facts, Asians seem uncomfortable with the very idea of a liberal education. Second, Yale-NUS has completely reimagined the curriculum of a liberal education (Click HERE). It wasn’t enough to merely introduce a controversial option for higher education; the Yale-NUS partnership completely redesigned what a liberal education should be for the 21st century!

By acknowledging our current “age of commodified information,” the Yale-NUS curriculum focuses on helping students learn how to think, not what to think. The focus is on methodology and process, not on specific facts. Departments don’t exist; and core classes address issues that transcend singular perspectives.

Consider one required course called “Current Issues” in which several faculty members address topics such as climate change, food, poverty, ageing, etc. from both scientific and social perspectives (click HERE). Without departments, cross-fertilization and collaboration around topics such as these are more likely and students acquire a depth of understanding that enables intelligent engagement on a broad range of topics.

The interdisciplinary curriculum emphasizes both breadth of exposure and rigor in methodology. As noted by the inaugural curriculum committee, “We do not put much value on broad but shallow learning. We aim, instead, to give depth to the breadth we offer.”

Yale-NUS College has the potential to transform higher education in the 21st Century by modeling a radically different approach to undergraduate education, but the experiment is not yet complete and cultural and social barriers still exist.

Of the 330 currently enrolled students at Yale-NUS College, 3% have chosen to drop out and leave the college, with several citing lack of specialization as a motivating factor (click HERE). Is this just a fundamental discomfort with the liberal arts model? After all, given that students are disproportionately occupied with required courses during the first two years, departing students may be leaving just before they begin to explore topics more deeply.

Is there an Asian cultural and social commitment to specialization and expertise that will take time to break?

Consider the most recent Programme for International Student Assessment (“PISA”) survey, a 2012 test administered by the OECD to more than 500,000 high school students in 65 countries (click HERE). At the top of the rankings for mathematics are China, Singapore, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan. The United States ranks 27th of the 34 OECD nations. The test is a measure of specific skills.

But as noted by Fareed Zakaria, despite this data, Americans believe they are the best in math…and it may be this self-esteem that allows Americans “to challenge their elders, start companies, persist when others think they are wrong, and pick themselves up when they fail”(click HERE). It drives American entrepreneurship.

Further, there is significant evidence that businesses prefer to hire smart and motivated individuals rather than those with specific skills to match current needs (click HERE). A recent survey conducted for the Association of American Colleges and Universities found that 93% of employers believe “a candidate’s demonstrated capacity to think critically, communicate clearly, and solve complex problems is more important than their undergraduate major” (click HERE).

So What? The 3% dropout rate for Yale-NUS bothers me. I believe Asia needs to look beyond the skills-based specialization models that dominate its educational landscape, and Yale-NUS offers one alternative. Asia seems destined to be a driver of the global economy for decades to come, and having a more dynamic and flexible labor pool will increase its resilience. Embracing liberal education in Asia offers the world a brighter future, one driven by more creative approaches to the world’s most pressing problems. I genuinely hope the 3% metric is an anomaly that will pass as the experiment progresses.

But I’m also hopeful Yale-NUS succeeds because it may provide a much-needed catalyst to change American higher education – it may catalyze greater interdisciplinary scholarship and teaching, a modification of the entrenched department-based fiefdoms and silos, and a general improvement in accountability. It may help implement the seemingly radical prescriptions in Columbia Professor Mark Taylor’s controversial New York Times piece “End the University as We Know It” (click HERE).

In today’s interconnected, dynamic, and rapidly shifting technological world, breadth of experience will soon trump depth of expertise (click HERE); the pendulum between specialists and generalists has swung too far towards specialists; the value of generalists seems poised to rise (click HERE for my 2012 HBR post “All Hail the Generalist”).

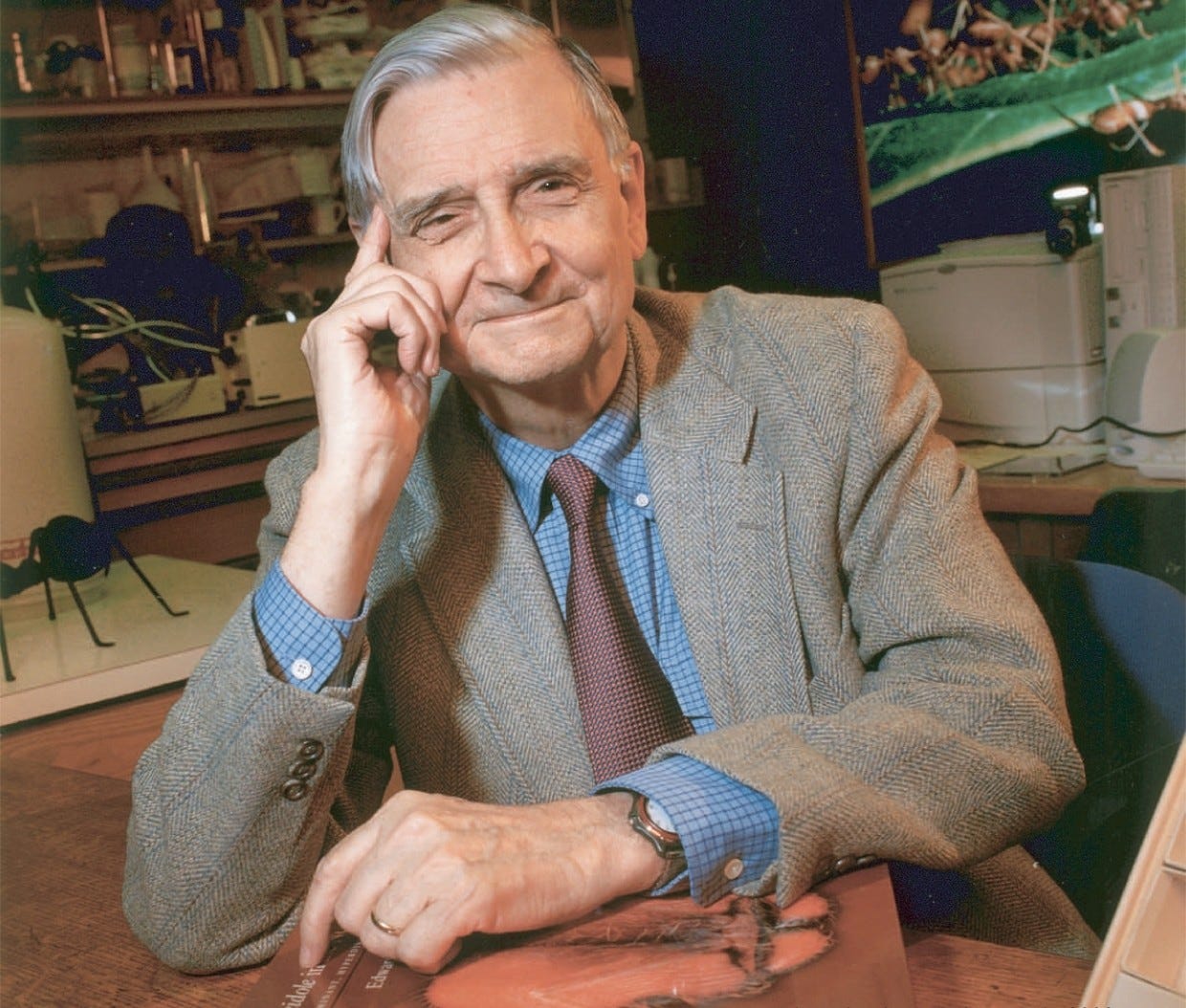

Given a key output of a liberal education is the ability to integrate perspectives, it’s worth noting Harvard biologist EO Wilson’s assessment of our most pressing problem: “We are drowning in information, while starving for wisdom. The world henceforth will be run by synthesizers, people able to put together the right information at the right time, think critically about it, and make important choices wisely.”

Vikram Mansharamani is a Lecturer at Yale University in the Program on Ethics, Politics, & Economics and a Senior Fellow at the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government at the Harvard Kennedy School. Visit his website for more information or to subscribe to his mailing list. He can also be followed on Twitter.