The Great Disconnect

The world seems very fragile right now. In the past week, North Korea claimed its missiles could reach the United States, spurring some in Congress to run through the calculus of striking the rogue nation before it attacks us. Pakistani courts ruled against Nawaz Sharif, the sitting prime minister, thereby forcing him to resign; Venezuela created an authoritarian regime that started cracking down on opposition leaders; Polish citizens were marching in the streets to protest proposed changes to the judiciary; HBO announced it had been the victim of a cyber attack that had stolen proprietary information; Russia began seizing American property and evicting US diplomats; and White House turnover continued unabated.

Oh, and Australian authorities stated they had thwarted a terrorist attempt to bring down a passenger aircraft. Last, but definitely not least, India and China flirted with military conflict over an unpaved road in a mountain pass in disputed territory in the Himalayan mountains.

And that was just in the past week!

Earlier in July, Brazil threw it’s ex-president Lula de Silva in prison, Saudi Arabia “reorganized” and installed the young and ambitious Mohammed bin Salman as Crown Prince, and Qatar’s airline was banned from flying in Egyptian, Saudi Arabian or Emirati airspace. Protests threatened instability in Morocco, Nigeria’s president Muhammadu Buhari has been absent for months, and South African president Jacob Zuma is facing a no-confidence vote this month.

Meanwhile, there are early warning signs that the world’s largest economy may be slowing. GM reported a 15% drop in US auto sales (with Ford and Chrysler also disappointing), and Fitch noted that credit card losses have been rising and recently hit a four-year high. And in an effort to address unemployment, Canada announced it’s experimenting with basic income programs. And China’s most recent manufacturing PMI came in below expectations, hinting at the possibility that China may be slowing down (although the country did just open a cinema on a disputed island in the South China Sea).

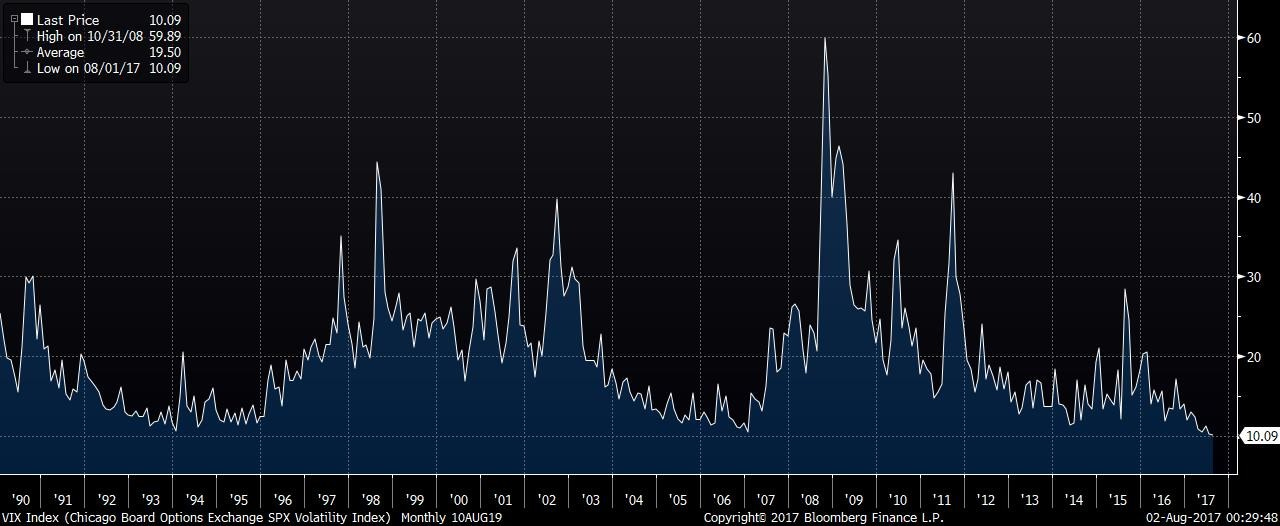

But despite these facts, financial markets have marched forward. Sure, corporate profits have been generally quite good, but does that justify today’s nonchalant attitude towards these risks? Just look at the CBOE Volatility Index (known among financial types as the “VIX”) hitting new lows. Believed by many to be a measure of fear among investors, the VIX recently fell below 10, a level rarely seen in the past few decades. The implication: investors are not generally worried.

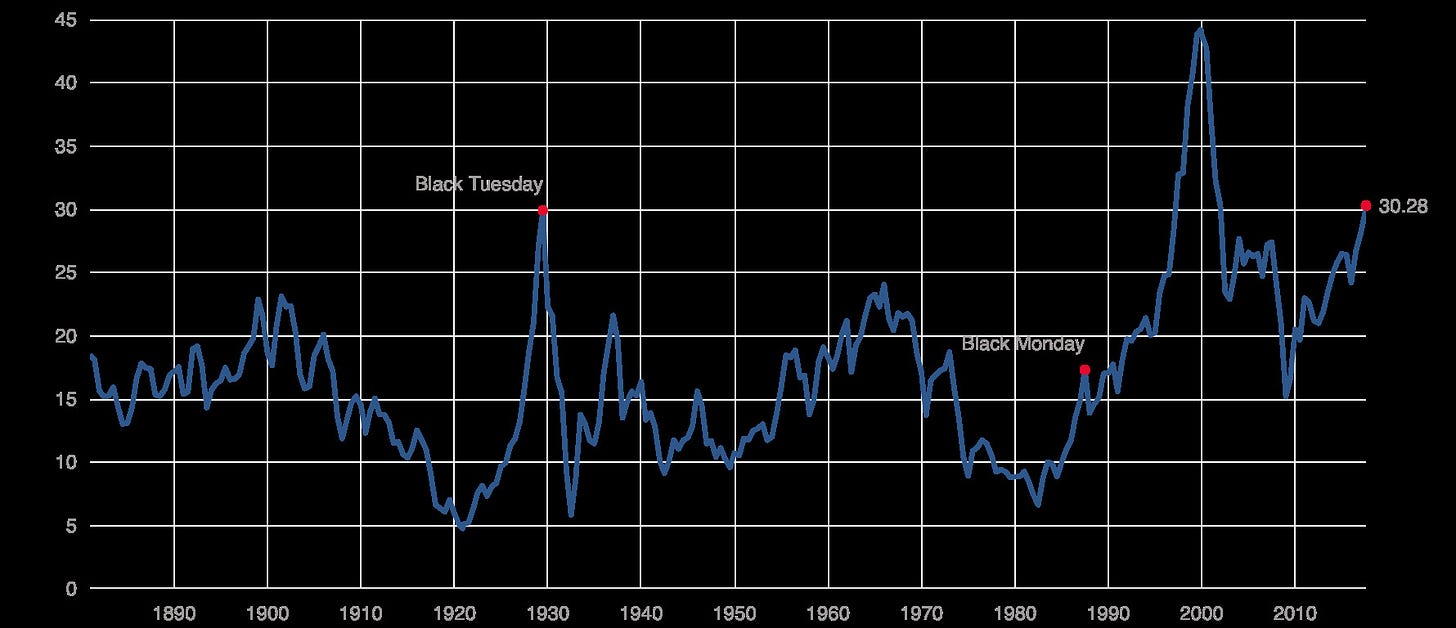

Further, the investment community appears more willing to pay handsomely for the profits companies produce. Consider the cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (aka the “CAPE” ratio), an admittedly imperfect, but useful, measure of valuation. The CAPE ratio recently crossed 30x, a level it rarely reaches.

And lastly, we have notable exuberance driving a formidable crypto-currency bubble, eloquently and persuasively documented by Laura Shin in a recent Forbes piece entitled “The Emperor’s New Coins.” Further, according to Coincap, there are currently more than 600 digital coins that in aggregate are supposedly worth more than $100 billion. And while blockchain technology will likely disrupt many businesses in the years to come, Shin’s article sheds light on the alarming speculative instincts that are thriving in the crypto-coin domain. If you haven’t read her article, I encourage you to do so.

So what am I missing?

The world seems to be precariously balanced on the edge, with instability lurking in almost every region of the globe, but financial markets seem not to care. Speculative instincts are running high and valuations today leave little margin of safety. It reminds of the 1980s song “It’s The End of The World As We Know It (and I Feel Fine)” by REM.

But surely there is a reason for the seeming disconnect, no? Might it be the devout faith in market efficiency? Could it be that the developments I’ve mentioned are fully factored-in to market prices? Might it be the powerful and undying love of passive investing that has led to a world in which more and more money is doing less and less analysis? Or does the explanation lie, as eloquently noted by Keynes ("Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally"), in the risk-averse career-driven decision making of those controlling financial assets? Or perhaps, to use four words that makes anyone who thinks of bubbles shudder, it’s different this time?

What do you think? Please let me know what you think.

Vikram Mansharamani is a Lecturer at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. He is the author of BOOMBUSTOLOGY: Spotting Financial Bubbles Before They Burst (Wiley, 2011). Visit his website for more information or to subscribe to his mailing list. He can also be followed on Twitter or by liking his Page on Facebook.