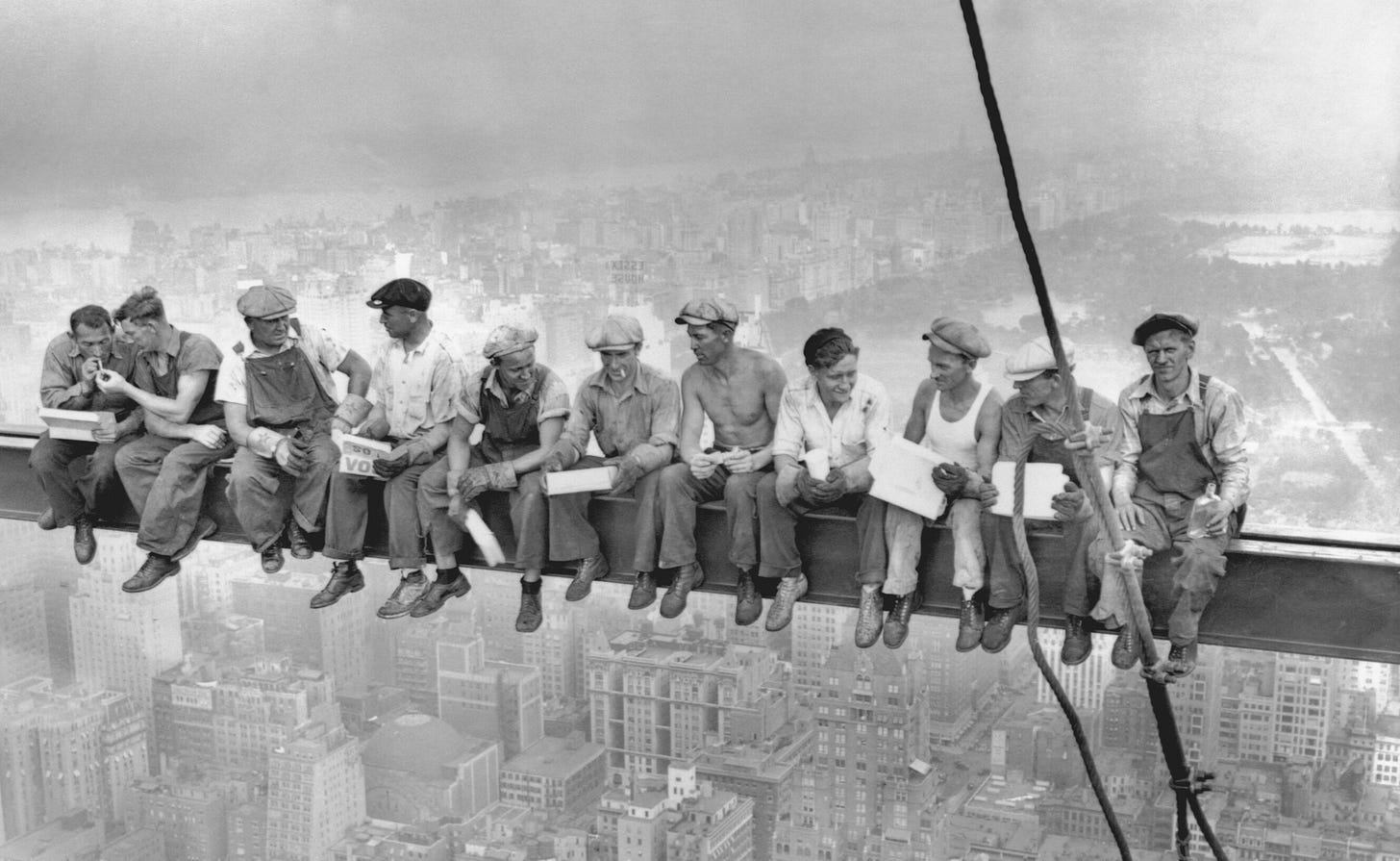

The Past, Present, and Future of Labor Unrest

Might rising inequality, worker shortages, and artificial intelligence be creating fertile ground for more frequent strikes?

As many of us fire up the grills for one last hurrah, it’s worth pausing for a minute to think about the purpose of Labor Day, our federal US holiday to celebrate the social and economic achievements of American workers. According to the US Department of Labor, “The holiday is rooted in the late nineteenth century, when labor activists pushed for a federal holiday to recognize the many contributions workers have made to America’s strength, prosperity, and well-being.” The holiday is also a useful catalyst to reflect on the history of and outlook for labor unrest.

While there are too many strikes in the United States to review, I want to highlight three big ones: The Pullman Strike, which led to the recognition of Labor Day as a federal holiday; the Coal Strike of 1902, which led to the US government playing the role of mediator; and the Air Traffic Controllers strike of 1981, which led to a multi-decade structural decline in the role of unions in America.

Labor Day was designated a national holiday by President Grover Cleveland amidst the Pullman strike of 1894, which some have called the “greatest strike in American history.” By the end of the three week strike, riots had spread nationally, federal troops were mobilized, workers lost more than $1 million in wages (~ $35 million in today’s dollars), damage exceeded $340,000 (~ $12 million in today’s dollars), railroads missed out on millions in revenues, and more than 40 died in clashes.

The federal government’s role in labor dispute mediation really began with the Coal Strike of 1902, in which anthracite coal miners organized by the United Mine Workers Union walked off the job. President Teddy Roosevelt tried to bring both sides together while acting as a neutral mediator, but failed. It took JP Morgan and other businesspeople to secure an end to the 163 days strike. The miners secured a 10% pay increase (they had requested 20%) and 9 hour workday (down from 10, but not the 8 they sought).

The Air Traffic Controllers strike of 1981, which began on August 3, 1981 when around 13,000 air traffic controllers walked off the job after efforts to negotiate higher pay and shorter workweeks failed. Thousands of flights were cancelled and President Ronald Reagan declared the strike illegal and said he’d fire anyone who wasn’t back at work within 48 hours. President Regan carried out his threat and added a lifetime ban on the Federal Aviation Administration ever rehiring a fired striker. More than 11,000 members of the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Association (PATCO) were fired.

For decades after the Air Traffic Controllers strike, labor unions were less compelling and the number of strikes begins to trail off. But more recently, we’ve seen a rebirth of organized labor, driven, in my assessment, by two major developments: (1) high and rapidly rising inequality and (2) COVID disruptions that motivated worker demands for better working conditions.

I’ve long believed that capitalism is the greatest form of economic organization on planet earth and has been a powerful force in raising the quality of life for millions of people. With that said, it isn’t perfect and has, from time to time, produced problematic levels of inequality, something many believe (including me) is the achilles heal of capitalism.

Karl Marx predicted that inequality would lead to the end of capitalism as it drove workers to unite and usher in a new world of harmony in which “from each according to their ability; to each according to their needs” became a prevailing mantra. In short, Marx believed capitalism would self-destruct through rising inequality and be displaced with a socialist utopia. It should be no surprise then that inequality drives unionization and collective bargaining efforts.

Marx believed capitalism would self-destruct through rising inequality and be displaced with a socialist utopia.

But over time, other factors have also played a major role in driving labor unrest. Whether it was hours per week, worker safety risks, or just some control over schedules, labor has long supplemented its desires for higher wages with a quest for more appealing conditions.

In fact, a recent CNBC piece highlighted how an almost perfect storm of conditions have driven labor unions to aggressively seek double-digit raises and better hours for their members:

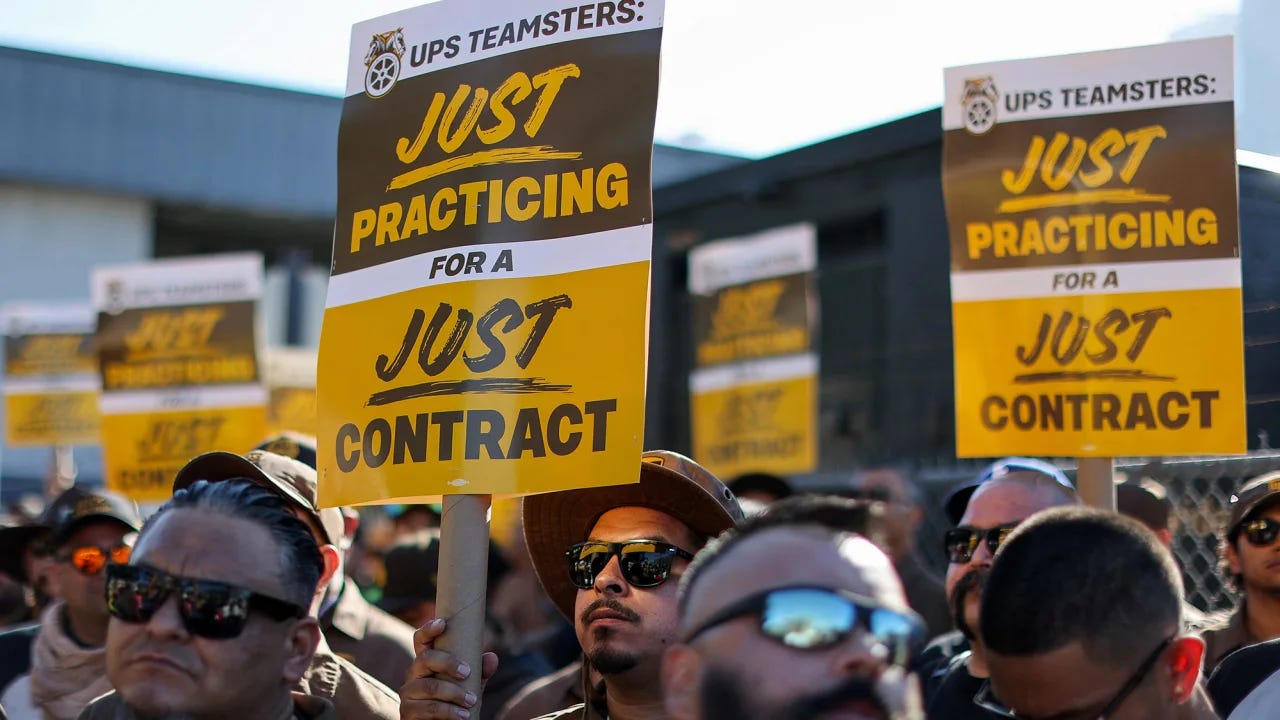

The poster child of success in this effort has been the International Brotherhood of Teamsters’ (IBT) success in negotiating with United Parcel Service (UPS). After the more than 340,000 union members working at UPS had authorized a strike to begin on August 1, the parties avoided a work stoppage after agreeing to higher wages, better working conditions, more work flexibility, and even an additional holiday. By the end of the five year agreement, average UPS driver compensation will be approximately $170,000 (including benefits).

Collective bargaining in the aviation sector has also led to some big wage gains. Pilots at United Airlines, for instance, were able to secure a 40% raise over 4 years, while those at Delta achieved a 34% raise over 4 years and American Airlines pilots obtained a 40% bump. The combination of pilot shortages, strong demand for air travel, and COVID related changes in working conditions gave the unions strong leverage to negotiate historic deals for pilots.

Similar dynamics have played out in many other sectors and labor unions have been noticeably active this year. Perhaps it’s because after decades of falling real wages, inflation and tight labor markets have driven workers to seek better? The Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations has reported that more than 320,000 workers have participated in more than 230 strikes so far this year. (That compares to around 240,000 workers in around 420 strikes last year.) Not all of these disputes have been resolved…

Think about what’s happening in Hollywood. In May, the Writers Guild of America (WGA) began a strike against the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP), about compensation related to streaming services and the risks to writers emerging from generative artificial intelligence. Then in July, the Screen Actors Guild and American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) went on strike given their own dispute with AMPTP. This is the first time since 1960 that both writers and actors have simultaneously walked out. And while there has been some negotiation in both of these disputes, both the writers and actors seem to be digging in for a prolonged fight. SAG-AFTRA is even contemplating an additional strike against video game makers.

It also appears that more strikes are possible. The United Auto Workers (UAW) for instance, represents more than 150,000 workers at General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis. They are in the midst of contract negotiations and have a deadline of September 14th to come to an agreement. Likely emboldened by other union successes, UAW President Shawn Fain has recently struck a combative tone and has filed an unfair labor practices claim against General Motors and Stellantis with the National Labor Relations Board. All of this suggests a likely strike of UAW members later this month.

A look back at history may provide a glimpse of what’s to come. Professor Joshua Freeman, a distinguished professor at the City University of New York who previously taught at Columbia University and has written extensively about the history of labor in America, gave a briefing on the History of Labor in the United States in July 2020 for the US State Department. During his presentation, he shared a fascinating fact that got little attention but struck me as potentially important: “The greatest strike wave in US history took place in 1919. One out of every five workers in the entire country went on strike…this actually overlapped with the worse pandemic in US history, the influenza epidemic of 1918, 1919.”

Could it be that the US is about to enter another “strike wave”? Could the risks to labor from the rise of artificial intelligence create a rapidly rising need for collective bargaining, bringing workers together in unexpected ways? Or could artificial intelligence simply increase inequality to the point that workers feel the need to unite and overthrow those in control? Is what’s happening in Hollywood a warning sign of what’s to come?

And even if formal union membership is not the mechanism for collective bargaining, might we get ad hoc groupings of workers for particular causes? Recall the Fight for 15, the campaign launched by fast-food workers seeking a $15/hr minimum wage. Even though it was supported by a union, growth in membership wasn’t the objective, political action was the goal. And it within a few years, they achieved their objective in several states. Is political action replacing collective bargaining as an objective of organized labor?

Finally, it’s interesting to note that the United States and United Kingdom had similar labor organization efforts in the late 19th century. In the America, this led to unionization that focused on collective bargaining to promote workers’ wages and better working conditions. The British effort went in a different direction, one that targeted political action, and led to the formation of the Labour Party. Even though American labor unions have historically chosen to align with established political parties, might they soon decide to step out on their own? Might current conditions in America be sowing the seeds of a new Labor Party in the United States?

There will always be a balancing act between the returns to labor and the return on capital. Let’s not forget, of course, that while wages are considered a cost in production, they are also the ultimate source of revenue for a company as well:

As The Economist magazine notes, “The original Henry Ford, committed to raising productivity and lowering prices remorselessly, appreciated this profoundly—and insisted on paying his workers twice the going rate, so they could afford to buy his cars.” It’s also the reason that General Motors was once known as “Generous Motors” and paid multiples of the minimum wage to their employees.

But as warned by many investment funds, past performance is not an indicator of future outcomes. The world is changing rapidly. Artificial intelligence is replacing labor and increasing output. Accelerating inequality is intensifying the pressures for collective bargaining. And COVID has changed the nature of work for many, driving a desire for greater autonomy and control over working conditions. Yet at the same time, a shortage of workers in many industries has improved the relative power of labor and created a situation where real wages for many industries are rising for the first time in decades.

These cross-currents have created profound uncertainty in labor markets, and while it’s impossible to know the outlook for labor unrest, one thing appears almost certain: organized labor is unlikely to disappear anytime soon.

About Vikram Mansharamani

Dr. Mansharamani is a global generalist who tries to look beyond the short term view that tends to dominate today’s agenda. He spends his time speaking with leaders in business, government, academia, and journalism…and prides himself on voraciously consuming a wide variety of books, magazines, articles, TV shows, and podcasts. LinkedIn twice listed him as their #1 Top Voice for Global Economics and Worth profiled him on their list of the 100 Most Powerful People in Global Finance. He has taught at Yale and Harvard and has a PhD and two masters degrees from MIT. He is also the author of THINK FOR YOURSELF: Restoring Common Sense in an Age of Experts and Artificial Intelligence as well as BOOMBUSTOLOGY: Spotting Financial Bubbles Before They Burst. Follow him on Twitter or LinkedIn.