The Student Loan Repayment Bomb

Repayments will likely threaten consumer spending and housing markets. Could they also be a catalyst for weaker job markets and a recession?

Regulators, policymakers, and analysts alike have been warning about outstanding student debt levels for years. Years before the pandemic, Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell had noted that student debt might restrict a borrower’s ability to start a business, finance a home purchase, or participate fully in the economy. In 2018, for instance, when student loan balances were ~$500 billion less than today, he warned if “student loans continue to grow and become larger and larger, then it absolutely could hold back growth.”

Student debt has ballooned to $1.8 trillion in 2023 (93% of which are federal student loans) and is now the second largest form of borrowing by US households behind mortgages. It’s almost double the $1 trillion of that American consumers had on their credit cards and significantly more than than the $1.5 trillion in debt used to purchase automobiles. And household debt (including mortgages and home equity lines of credit) currently totals over $17 trillion, a record level. Inflation, of course, has been a major contributing factor to all debt balances, as consumers borrowed increasingly larger sums to finance the rapidly rising prices of cars, homes, and educations.

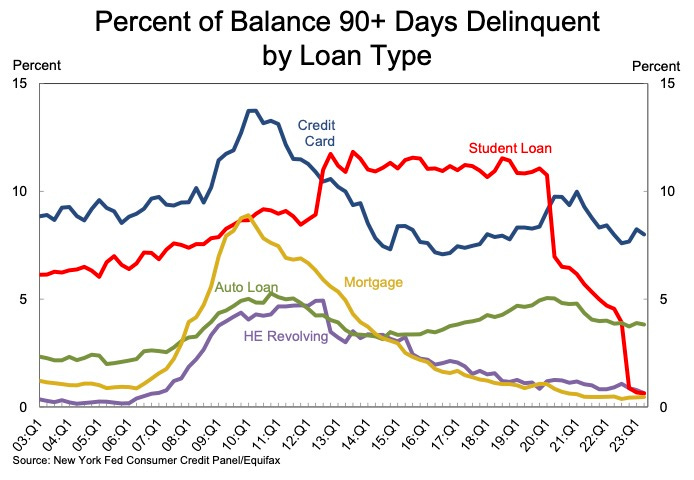

The idea behind student loans was sound. “Borrow money, invest in yourself, and your post-education income gains will more than offset the cost of the loans” was the logic. And for many students, that was indeed the case. But as tuitions rose far more rapidly than inflation, and the number of students seeking educational opportunities rose, the economic return for many students fell below the cost of debt. Prior to the pandemic, student debt delinquencies were consistently above 10%, many times higher than those for mortgages or automobiles.

During the pandemic, in a quest to support consumers in the midst of a potential economic collapse, the Department of Education (ED) reduced the interest rate for qualifying student loans to 0% from March 13, 2020 through August 31, 2023. Further, all borrowers were also granted an “administrative forbearance” that paused any required payments until October 1, 2023. Unsurprisingly, student loan delinquencies fell to almost zero while the delinquency rates for credit cards and automobiles have reverted to pre-pandemic levels. This led to improving credit scores for many borrowers, a dynamic that enabled them to borrow even more money.

Further, because of how many mortgage issuers calculate creditworthiness and debt-to-income ratios (thanks to Obama-era income-based student loan repayment schemes), many also believe the student loan bubble helped inflate a housing bubble. A recent Wall Street Journal article provided a clear example:

As the policies which allowed borrowers to forego required repayments end, the implications for the US economy are not good. Simple math can help us guesstimate the impact. To calculate the annual interest owed on student debt, let’s conservatively assume a 5% rate (many loans are above this level): $1.8 trillion times 5% = $90 billion. In addition to interest, borrowers need to repay principal, which suggests that the 43.6 million consumers who have federal student loans will need to divert at least $100 billion annually from buying goods and services to repaying debt.

Perhaps this is why the Biden administration tried to forgive more than $400 billion of debt. In August 2022, “President Biden told federal student loan borrowers that the U.S. government would cancel up to $20,000 of debt for low income students who had received a Pell Grant to attend college, and up to $10,000 for the vast majority of remaining borrowers.” The plan would have been a federal handout to more than 43 million borrowers, or approximately 13% of Americans. Several states immediately contested the legality of the Biden plan and the case quickly found its way to the highest court in America. In June 2023, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled against the Biden-Harris plan to forgive student loan debt for millions of borrowers.

Student loan repayments are set to restart next month. While it’s impossible to know how this development will impact the economy as a whole, it’s worth considering a few (of the many) possible implications:

It seems highly likely that consumer creditworthiness will fall as student loan delinquencies rise. What will deteriorating credit scores mean for the ability of consumers to borrow, or the rates at which they can borrow? Is it possible that demand for durable consumer goods plunges? How will this impact the current wave of labor unrest?

As consumers spend more than $100 billion to repay student debt, will the corresponding fall in demand for goods and services be the straw that breaks the economic camel’s back? If consumers slow spending enough to meaningfully impact business profits, will unemployment rise? Could student loan repayments derail the strong labor market?

Could the pandemic housing boom have been partially driven by student loan forbearance? Will the resumption of student loan repayments put sufficient stress on over leveraged households that mortgage delinquencies rise, and might the already fragile real estate market crumble? Are the rapidly falling home prices in the San Francisco Bay area an early warning indicicator for housing in general?

Could a forthcoming recession impact the US Presidential election of 2024? A recession during the second half of President George H. W. Bush’s first term set the stage for Bill Clinton’s winning campaign that focused on the economy. Might a combination of falling housing prices, a rapidly weakening housing market, and strained household budgets doom a Biden re-election?

Regardless of what transpires, the combination of elevated household debt levels and interest rates that have risen rapidly are a toxic cocktail that could derail the economy. The impact of higher interest rates are rarely felt instantaneously; rather, the higher cost of money hits consumer budgets over time as homeowners move or families replace worn-out durable goods such as cars and appliances. Might our economy be like Wile E. Coyote who has run off a cliff, his feet are still moving, but he has yet to look down? Only time will tell.

About Vikram Mansharamani

Dr. Mansharamani is a global generalist who tries to look beyond the short term view that tends to dominate today’s agenda. He spends his time speaking with leaders in business, government, academia, and journalism…and prides himself on voraciously consuming a wide variety of books, magazines, articles, TV shows, and podcasts. LinkedIn twice listed him as their #1 Top Voice for Global Economics and Worth profiled him on their list of the 100 Most Powerful People in Global Finance. He has taught at Yale and Harvard and has a PhD and two masters degrees from MIT. He is also the author of THINK FOR YOURSELF: Restoring Common Sense in an Age of Experts and Artificial Intelligence as well as BOOMBUSTOLOGY: Spotting Financial Bubbles Before They Burst. Follow him on Twitter or LinkedIn.