To Fix Europe, Break It

Last week, British Prime Minister David Cameron negotiated a deal with his fellow Europeans that may save the EU—or, more likely, accelerate its demise. It was Cameron’s mission to extract more favorable terms for his country. The Prime Minister emerged from the talks with an agreement that, among other things, allows the UK to cut benefits received by migrant EU workers. While British Eurosceptics—including six of Cameron’s senior ministers—saw the deal as more form than substance, their Continental neighbors understood the significance of granting these special privileges to a member country. Some fear it to be a “kiss of death” for the European experiment.

Now, Cameron has set a date—June 23rd—for a referendum on his country’s membership in the EU, given the concessions—or lack thereof, depending your point of view—that he obtained. The Prime Minister will campaign for Britain to remain in the Union, while Boris Johnson, the popular mayor of London (and potential Cameron successor), will urge his compatriots to leave.

The fundamental issue at hand, which the UK’s status within Europe obscures, is that monetary union without political integration generates tension and instability. Just consider the havoc wreaked by Europe’s equivocal approach to unification. Countries like Greece are stuck with an overvalued currency that makes them uncompetitive, while richer nations like Germany are made ultracompetitive by a de facto undervalued currency. The situation creates tremendous pressure on the system, with no meaningful ways to resolve imbalances except through counter-productive austerity measures.

By contrast, the United States of America, which integrated politically and monetarily, does not have these problems, despite large disparities in federal tax contributions and benefits between states. Given the European experience, I suspect potential future monetary unions, like the Gulf Common Currency, that lack the political integration of the US, but whose states could benefit from independent monetary policy, will not get far.

The European economic outlook is dire. Countries like Italy and Greece rank low in economic freedom. Growth is anemic, and Greece remains stuck in recession, with farmers clashing with police in recent weeks over austerity measures. Unemployment in Europe is high—averaging 10.4%, but reaching 25% in Greece. Further, a million migrants entered the region in 2015, and states have struggled to respond. It’s only getting worse, and the dynamic is adding pressure on states to erect impenetrable national borders.

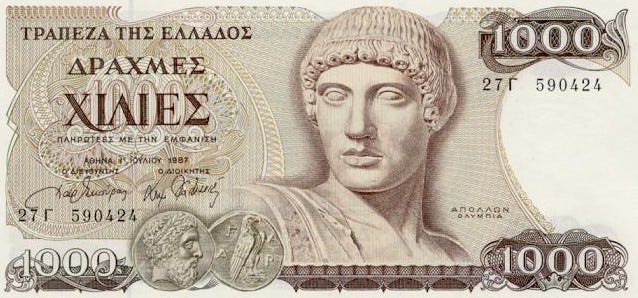

For these reasons, the European Union—a historically unique attempt at bloodless state formation—is at an inflection point. It is very unstable today and will either politically integrate into a “United States of Europe,” as Winston Churchill put it, or revert to the land of drachmas, marks, francs, and solid borders. I’m not betting on an outcome, but if I were, it would be on the dissolution of the common currency within the next 10 years.

I’m not betting on an outcome, but if I were, it would be on the dissolution of the common currency within the next 10 years.

If the EU must move decisively towards an “ever closer union” to survive, the provision granted to the UK last week may be a harbinger of disintegration. Cameron’s success in obtaining language that frees the UK from any obligation of “further political integration” sets a precedent. The concessions imply a wounded Brussels desperately clinging to the hope of union. It’s a not-so-subtle admission that the European experiment is failing, that political union appears unachievable.

Elsewhere on the continent, French Eurosceptic Marine Le Pen, who is running for President in 2017, promises to lead a “Frexit” referendum. The Dutch and Italians are also harboring strong anti-European movements.

Whether or not countries actually leave the EU, Cameron’s gambit has paved the way for members to extract concessions from Brussels by threatening a referendum, potentially dooming the idealistic dream of a coherent European superstate.

Given the political barriers to further integration, the best strategy may well be to dissolve the Euro, and perhaps with it the European Union—at least in its original conception. Doing so might enable the restoration of democratic legitimacy, and the re-emergence of independent monetary controls might help improve the region’s economic outlook. Greece, for instance, would regain control of its own fiscal and monetary policy. Despite having seen its GDP shrink by one-third, a depreciated drachma 2.0 might increase the appeal of Greece in a global economy, quite possibly putting it on a path to a sustainable recovery.

The pressures on the economies of Europe are unlikely to dissipate anytime soon. As such, it's time to admit the unification experiment isn't working and that to fix Europe, we likely need to break it.

Vikram Mansharamani is a Lecturer at Yale University in the Program on Ethics, Politics, & Economics. He is the author of BOOMBUSTOLOGY: Spotting Financial Bubbles Before They Burst (Wiley, 2011). Visit his website for more information or to subscribe to his mailing list. He can also be followed on Twitter or by liking his Page on Facebook.